The journey of chopsticks from rudimentary cooking implements to refined dining instruments spans over three millennia, weaving through cultural revolutions, culinary evolution, and profound shifts in social etiquette. Unlike many everyday objects whose histories fade into obscurity, the story of the chopstick is a vibrant tapestry reflecting the very heart of East Asian civilization. Its design, seemingly simple and unchanging, has in fact been in a state of continuous, subtle refinement, perfectly adapting to the changing needs of the people who wield it.

Long before they touched the lips of emperors or commoners, the earliest precursors to chopsticks were likely simple twigs or branches used to manipulate food over open fires. The earliest archaeological evidence, from the Shang Dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BCE), points to their primary use as cooking tools. These bronze implements, longer and sturdier than their modern counterparts, were perfect for reaching into deep pots of boiling water or oil to retrieve morsels of food without scalding one's hands. This utilitarian beginning established the chopstick's fundamental principle: an extension of the hand designed for precision and safety in the presence of heat.

A pivotal shift occurred during the Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 BCE), a period renowned for its philosophical flourishing and codification of rituals. It was here that chopsticks began their transition from the hearth to the table. The rise of confucian ideals, which emphasized frugality and condemned the extravagance of large knives at the dining table, played a significant role. Knives were associated with the butcher's trade and warfare, deemed too violent and vulgar for the civilized setting of a meal. Chopsticks, in their elegant simplicity, became the civilized alternative, reflecting a cultural move towards harmony and refinement at mealtimes.

Concurrently, a culinary revolution was underway. The widespread adoption of grain-based diets, particularly millet and rice, provided the perfect foodstuff for chopsticks. These small, bite-sized staples were ideally suited to being pinched and lifted, unlike bread or large cuts of meat that required tearing or slicing. Furthermore, the popularization of stews and chopped dishes, where ingredients were pre-cut in the kitchen into manageable pieces, rendered the individual diner's knife obsolete. The meal became a communal and peaceful experience, with chopsticks serving as the primary conduit from bowl to mouth.

The Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) cemented the chopstick's status as the premier eating utensil across all social strata. Lacquerware, a technological marvel of the time, allowed for the production of lighter, more beautiful, and more durable chopsticks. Artisans began crafting pairs from a diverse array of materials including bamboo, wood, bone, and even precious metals and jade for the aristocracy. The design began to standardize in length and taper, moving away from the purely functional tools of the kitchen to objects that also pleased the eye and the hand. This period marked the chopstick's full maturation into an essential餐具 (cān jù - eating utensil).

As chopstick culture spread from its Chinese heartland to Korea, Japan, and Vietnam, it diversified, each region imprinting its own aesthetic and functional preferences onto the design. In Japan, where a strong tradition of individual place settings developed, chopsticks became shorter, sharper, and more pointed, often made from lacquered wood or bamboo. The Japanese also pioneered the disposable waribashi, split from a single piece of wood, reflecting different social and hygienic considerations. Korean chopsticks, by contrast, were often fashioned from metal, typically brass or stainless steel. This tradition is thought to have originated from the use of silver chopsticks by the nobility to detect poison in their food, as certain toxins would cause the silver to discolor. Their flat, rectangular shape provides a unique grip. Vietnamese chopsticks tend to be longer and made of plain wood or bamboo, a design influenced by their prevalent communal dining style where one needs to reach across the table.

The evolution of the chopstick is also a story of artisanal craftsmanship and symbolic meaning. For centuries, creating a pair was an art form. Master craftsmen would select materials for their grain, weight, and balance. They were often intricately decorated with calligraphy, landscapes, or auspicious symbols, transforming them into cherished personal items or valuable gifts. They became embedded in folklore and superstition; tapping them on the bowl was associated with beggary, and sticking them upright in a bowl of rice was a powerful funerary symbol, strictly avoided in daily life. They were more than just tools; they were cultural signifiers.

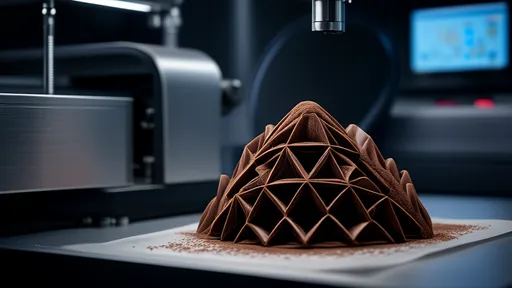

The advent of the 20th and 21st centuries brought industrialization and globalization, presenting both challenges and new chapters in the chopstick's story. The mass production of disposable chopsticks, primarily in China and Japan, addressed hygiene concerns in restaurants but sparked major environmental debates over deforestation and waste. In response, there has been a modern push towards sustainability, with innovations including reusable travel chopsticks, pairs made from recycled materials, and a renewed appreciation for finely crafted, lifelong sets. The design continues to evolve, with ergonomic grips and specialized tips for everything from eating noodles to typing on a touchscreen without removing one's gloves.

From a pair of charred twigs by a primordial fire to the sleek, manufactured, or hand-carved instruments of today, the chopstick's three-thousand-year journey is a remarkable narrative of adaptation. It is a design that has successfully navigated the transition from kitchen implement to cultural icon, all while retaining its core principle of elegant simplicity. It has shaped dining customs, inspired artisans, and connected hundreds of generations to their food and to each other. The humble chopstick stands not as a relic, but as a enduring and evolving testament to human ingenuity and cultural identity.

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025