In the hushed corridors of food innovation labs and the bustling markets of Southeast Asia, a quiet revolution is taking place. It’s not about a new superfruit or a lab-grown steak, but something far more ancient and, to many Western palates, far more challenging: insects. The notion of entomophagy—the practice of eating insects—has been a staple for billions around the globe for millennia. Yet, in Europe and North America, the idea often elicits a visceral shudder, a deep-seated cultural aversion that labels insects as pests, not pantry items. The question that researchers, entrepreneurs, and environmentalists are now grappling with is not about the nutritional value or sustainability of insect protein—both are well-established—but about perception. How do we make the consumption of insects not just acceptable, but normal?

The journey to normalization is, first and foremost, a battle against the ick factor. This immediate, almost primal disgust is perhaps the single greatest barrier to widespread adoption in Western societies. It’s a complex emotion, woven from threads of cultural conditioning, unfamiliarity, and a deep-rooted association with dirt and disease. We are taught from a young age that flies are unsanitary, that ants ruin picnics, and that cockroaches are the ultimate sign of an unclean home. To then pivot and present these creatures as food requires a fundamental rewiring of deeply ingrained attitudes. This isn't a simple marketing problem; it's a psychological and cultural one.

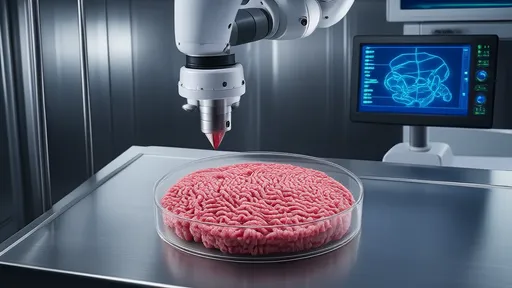

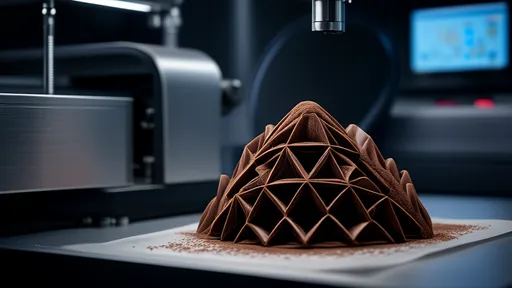

One of the most promising strategies to overcome this hurdle is invisibility. Rather than presenting whole, fried crickets as a bar snack—a bold move that appeals to adventurous eaters but terrifies the mainstream—companies are focusing on insect-derived ingredients. The goal is to harness the nutritional power of insects without triggering the disgust response. Cricket flour, for instance, is a fine, nutty-tasting powder that can be seamlessly incorporated into familiar foods: protein bars, pasta, baking mixes, and burger patties. When a consumer bites into a delicious chocolate chip cookie, they are experiencing taste and texture they know and love. The fact that it contains 10% cricket flour is a secondary, intellectual benefit—high protein, sustainable—that doesn’t interfere with the primary sensory experience. This approach doesn’t ask people to overcome their fear; it simply makes it irrelevant.

Beyond hiding it in plain sight, there is a parallel effort to reframe the narrative surrounding insects. The language used is crucial. Calling it bug eating reinforces the taboo. Instead, the industry is adopting more technical and appealing terms like cricket powder, insect protein, or alternative livestock. The messaging is strategically shifted from the weird and novel to the sensible and sustainable. Marketing campaigns focus less on the creature itself and more on the positive outcomes: the incredibly efficient feed-to-protein conversion ratio (crickets require twelve times less feed than cattle to produce the same amount of protein), the minimal land and water requirements, and the reduced greenhouse gas emissions. It becomes a choice for the environmentally conscious consumer, a logical and ethical decision rather than a dare.

This rebranding effort extends to packaging and design. Startups in this space are investing heavily in sleek, modern, and attractive packaging that wouldn’t look out of place in a high-end wellness store. The imagery is of vibrant smoothie bowls, artisanal bread, and athletic people hiking—not a close-up of a cricket’s leg. The product is positioned alongside other accepted health foods like chia seeds, spirulina, and quinoa, borrowing from their aura of superfood status. The subliminal message is clear: this is not a novelty item for a dare; it is a premium, forward-thinking nutritional choice for modern, healthy living.

Another powerful tool for normalization is culinary integration. The history of food is a history of adopted foreign delicacies that eventually become mainstream. Sushi, once considered exotic and strange in the West, is now a ubiquitous lunch option. The same path is being paved for insects, starting at the top of the culinary world. Renowned chefs at trendy restaurants are introducing insect-based dishes as gourmet, high-end experiences. A taco with chapulines (grasshoppers) or a delicate amuse-bouche featuring ant caviar becomes a talking point, an experience of luxury and adventure. This top-down influence lends an air of sophistication and credibility, trickling down trends to the home cook and the mass market. When a respected chef treats an ingredient with reverence, it begins to strip away its negative connotations.

Ultimately, the most potent agent of change may be the simplest: the next generation. While adults carry decades of cultural baggage, children are far more malleable in their food preferences. Educational programs that introduce the environmental benefits of insect farming, coupled with tastings of cricket-flour brownies in schools, can plant seeds of acceptance early on. For these children, insects as food won’t be a strange concept they have to unlearn; it will be a normal, even boring, fact of life. They are the future consumers for whom the ick factor may not exist at all, making the entire endeavor not a battle of persuasion but one of simple education.

The path to normalizing insect protein is a multifaceted one, weaving together psychology, marketing, gastronomy, and education. It requires a respectful understanding of deep-seated cultural aversions and a clever, nuanced approach to circumventing them. The solution isn't to force a plate of whole insects in front of someone and demand they get over it. It is to slowly, patiently, and intelligently integrate this ancient, sustainable source of nutrition into the very fabric of our modern food system, until one day we look back and wonder what the fuss was ever about.

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025