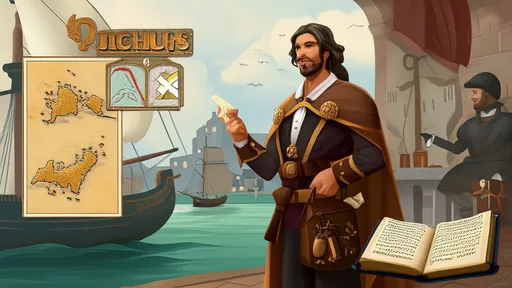

For generations, a charming tale has been woven into the fabric of culinary history: the story that Marco Polo, the famed Venetian explorer, brought pasta to Italy from China in the late 13th century. It’s a narrative that has been served up in classrooms, cookbooks, and dinner table conversations around the world. Yet, like many good stories, this one appears to be more legend than fact—a delicious myth that has persisted far longer than it should have.

The origins of this belief are murky, but it seems to have gained significant traction in the 20th century, particularly within popular culture. Many point to the 1920s or 1930s, when a widely circulated advertisement for a pasta company in North America allegedly used Marco Polo’s journey as a marketing gimmick. The image of the adventurous trader introducing such a beloved staple made for compelling storytelling—and excellent brand recognition. From there, the idea seeped into the public consciousness, becoming accepted as truth by many who never stopped to question its validity.

However, the historical record tells a different, far more complex story—one that begins long before Marco Polo was even born. Evidence of noodle-like foods exists in various ancient cultures, from the Middle East to Central Asia. But crucially, in Italy itself, there are clear references to a food resembling pasta dating back centuries earlier than Polo’s travels.

One of the most definitive pieces of evidence comes from the writings of the Arab geographer Al-Idrisi. Working in the 12th century under the rule of Roger II of Sicily, he documented that in the town of Trabia, just outside Palermo, a food made from flour in the shape of strings was produced in large quantities and exported to other regions. He called it itrya—a term derived from Arabic, which referred to a type of dry pasta. This account, written a full century before Marco Polo’s return to Venice, clearly places pasta production on Italian soil long before his famed expedition.

Furthermore, in the decades before Polo’s journey, notarial records in Genoa and other Italian regions occasionally mention items such as macaronis—a term that likely referred to dried pasta shapes. These documents, often inventories or wills, indicate that pasta was not only known but was sometimes considered a valuable enough commodity to be itemized among personal possessions.

So where does China fit into all of this? It is true that China has an ancient and rich tradition of noodle-making, with archaeological evidence dating back thousands of years. Marco Polo did indeed travel to China and would certainly have encountered noodles there. In his famous book, The Travels of Marco Polo, he describes a plant from which the Chinese made something like barley flour—a possible reference to sago palm starch used in some noodle preparations. But notably, he never explicitly states that he brought back pasta or its concept to Italy. The leap connecting his description to the introduction of pasta appears to be a later invention.

In reality, the development of pasta in Italy and noodles in China likely occurred independently, as part of parallel culinary evolutions. Both cultures discovered that mixing ground grains with water created a versatile dough that could be dried, stored, and cooked in numerous ways. It was a practical solution to preserving food and making the most of agricultural products—a convergent innovation rather than a case of cultural transplantation.

Another critical factor in the evolution of Italian pasta was the introduction of durum wheat—a hard wheat variety ideal for producing dry pasta—to Sicily and Southern Italy via Arab traders. The Arabs, who ruled Sicily for centuries, brought with them advanced agricultural techniques and food preparation methods, including the know-how to make dried pasta. This exchange predates Marco Polo by hundreds of years and represents a far more plausible origin for the pasta-making tradition that would eventually sweep across Italy and the world.

By the time Marco Polo returned to Venice in 1295, pasta was already being produced in several regions of Italy. It wasn’t a novelty he introduced, but rather a food that was gradually becoming more refined and widespread thanks to trade, agricultural development, and culinary experimentation within the Mediterranean world.

Why, then, has the Marco Polo myth endured for so long? Humans are natural storytellers, and we are often drawn to simple, elegant narratives over messy, complicated historical truths. The idea of a single heroic figure responsible for gifting the world one of its most beloved foods is far more romantic than the gradual, collective process of culinary evolution involving countless unnamed farmers, traders, and cooks. The myth also fits neatly into a broader narrative of East-Meets-West cultural exchange, making it an appealing tale in an increasingly globalized world.

In recent decades, historians and food scholars have worked diligently to set the record straight, publishing detailed research that debunks the Marco Polo pasta legend once and for all. Yet, as with many long-held beliefs, the myth proves stubborn. It continues to pop up in articles, documentaries, and even educational materials, demonstrating the powerful grip that a good story can have on our collective imagination.

So the next time you enjoy a plate of spaghetti carbonara or a bowl of penne arrabbiata, you can appreciate the true history behind it—a history not of a single moment of discovery, but of centuries of cultural exchange, agricultural innovation, and culinary creativity across the Mediterranean. And while Marco Polo’s travels remain an incredible feat of exploration, his story and the story of pasta are best understood as separate, if occasionally overlapping, chapters in the rich history of human civilization.

The tale of Marco Polo and pasta serves as a reminder to question what we think we know about history—especially when it comes to the origins of our favorite foods. Often, the truth is more complex, more collaborative, and in many ways, more interesting than the myths we replace it with.

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025